Over the past 50 years, there has been an evolution of psychotherapy reflected in the authors and publications found in the journal. The evolution can be seen both in the careers of long-standing clinicians whose ideas have grown or shifted across many years of clinical practice and in the evolution across different processes, theories, and styles of work in the field of psychotherapy.

Over the years, the therapeutic focus and theoretical orientation has evolved across the life of the journal. Early issues published many papers that involved speculative theories based on case examples that were proposed by lifelong clinicians. Sometimes, these clinical perspective papers were supported by detailed case studies. Many of the early articles were written by a single author who took the time to share their professional experience, theoretical views and informed opinions. More recently, journal articles rely on established theories and empirical research to support their claims. Today, most papers are being written by a collaborative team of co-authors and investigators, with few pure clinicians submitting manuscripts based on their own work in the clinical practice of psychotherapy.

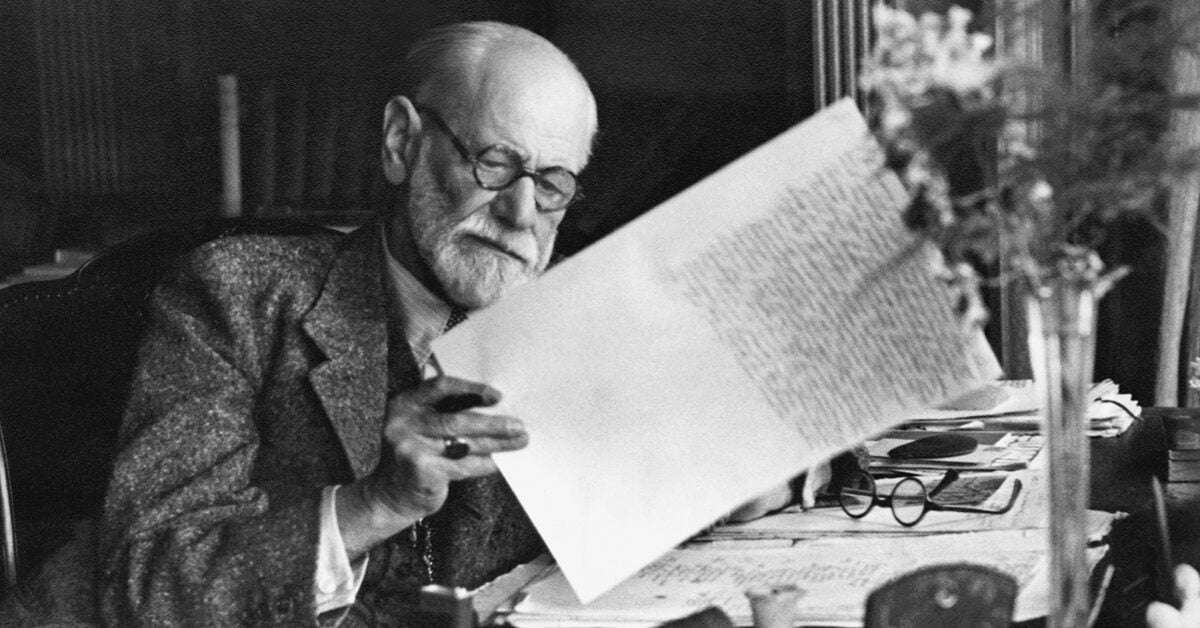

Some respected authors have described their psychotherapy knowledge, skill and style that has evolved over the course of their career (e.g., Ekstein 1973; Whitaker 1973). For example, Mowrer (1973) described the enhanced modesty that developed over the past 10 years of his career. Mowrer (1973) explained that his view of psychotherapy developed during his undergraduate schooling and graduate training, sparking his early interest in psychoanalysis. However, over time, his faith in the psychoanalytic approach was shaken because of limited research support as well as his own unsuccessful time as a psychoanalytic patient. In a similar vein, Strupp (1971, p. 117) noted: “Once in the forefront of revolutionary change, psychoanalysis is with increasing monotony described as antiquated, passé, obsolete, and even defunct … its therapeutic effectiveness has been questioned; its applicability to the vast problems of contemporary society is being doubted; and its status as a branch of the behavioral sciences appears to be approaching a nadir”. This sad statement reflects some long-standing concerns with older theories, potentially encouraging innovation and evolution within the field of psychotherapy. As noted by Strupp (1971, p. 118), “the basic problem … lies in the failure of psychoanalysis to have cultivated a spirit of open inquiry, a chronic unwillingness to welcome new ideas and techniques no matter where they might come from, a pervasive disinclination to question time-honored ideas and practices … the science of psychoanalysis has been treated as the private property of a professional guild”. Again, these ideas should help to promote, if not provoke, more collaborative work and diverse approaches to psychotherapy.

In contrast, some expert psychotherapists developed their ideas about psychotherapy early in their career, and remained staunch advocates of one particular approach. For example, Eysenck (1973, p. 22) claimed that “My approach to psychotherapy has not changed in the slightest since my first visit to the U.S.A.” Furthermore, Eysenck (1973, p. 27) encouraged integrative approaches to psychotherapy, stating “perhaps the time has now come for a dialogue aimed at setting up a unified discipline of psychotherapy of which we can all be proud”. Others (e.g., Greenwald 1971) also encouraged the integration of different theoretical models.

The importance of a solid therapeutic alliance is one aspect of psychotherapy that has remained respected over the years. Bowlby (1970) emphasized the importance of early bonding experiences on adult relationships. In a thoughtful review of his life and career, Wolpe (1973) emphasized the central value of the therapeutic reliance as a healing factor for most clients. Despite being a staunch advocate for the behaviorist movement, Wolpe respected the value of the therapeutic relationship. “The behavior therapist approaches his patients in a warm and friendly way that accords his conception of them as sufferers from unfortunate habits that they cannot help” (Wolpe 1973, p. 61). Likewise, Frank (1974, p. 118) noted: “Characteristics of the therapist related to his success are, a strong interest in his patients, ability to inspire their trust, and capacity to grasp what they are trying to say and reflect it to them”. However, it was noted that a caring relationship was not enough for effective therapy, but the therapist needed to instill the courage needed to help clients grow through their pain (Whitaker 1973).

Cognitive-behavioral approaches have grown in strength because of the importance of research, and the willingness to examine critically what works and why it works. As noted by Strupp (1971, p. 120): “psychoanalysis has lost its scientific respectability in 1970 and, in many quarters has been degraded to an esoteric pursuit of a small cult who cater to affluent members of the upper middle class. …. The key is to be found in the abandonment of a smug attitude of narcissistic omnipotence”. Sadly, today, this statement may now apply to cognitive-behavioral therapy, which is often seen and taught as the only approved form of psychotherapy.

Currently, the field of psychotherapy strives to meet the demands of evidence-based practice. Therefore, treatment manuals have been playing an important role in research, helping to ensure that each client in the study receives the same, or very similar treatment. Without such structured interventions, it can be difficult to objectively describe and replicate the treatment even when it has been found effective in reducing clients’ symptoms. Unfortunately, when trainees and clinicians believe that all clients must be treated in a rigidly structured manner, then the unique adaptations and idiographic creativity are lost. There is a risk that clinical judgment will be devalued, and psychotherapists could be viewed as paraprofessional technicians guided by a manual (Shedler 2018). The current emphasis on evidence-based practice relies heavily on treatment manuals (Shedler 2018). However, manualized treatment has not been found to be more effective than traditional fluid styles of psychotherapy that remain more idiographic in their application (Shedler 2018; Truijens et al. 2019). Furthermore, it appears that degree of adherence to the manual does not have a significant impact on its effectiveness (Truijens et al. 2019). Finally, the importance of a client’s subjective experience may be overshadowed by a focus on “objective” reality (Bugental 1969). Therapy can help clients become more aware of the subjective feelings, and learn to understand, accept, and express their emotions in a constructive manner (Greenberg 2006; Pos and Greenberg 2007). Although research often requires therapists to adhere to strict standards for each session, it seems more appropriate to allow a certain degree of flexibility to adapt a structured treatment plan to the unique needs of each client, perhaps guided by thematic modules. As noted long ago (Wolpe 1973). It is a mistake to view behavioral interventions as mechanically applied. Ekstein (1973) describes the therapist’s role as analogous to a servant, who waits to find out what is needed and participates by serving a meal without manipulating the guest.

The field of psychotherapy continues to evolve. As the published articles become more heavily anchored in science, there is a risk that the notions become further removed from clinical practice. Many innovative papers are being published about the benefits of technology adapted psychotherapy (TAP: Overholser 2013), including internet-based information programs and smart phone applications that might help to educate clients. These technological advancements can help therapists to engage with youthful clients or connect with clients who struggle with mobility, transportation, or child care. It is important to use technology as a supplement to session dialogue so the field does not neglect the central importance of a strong therapeutic alliance as a vital ingredient in effective psychotherapy. As noted by Wolpe (1973, p. 59), “The common feature of all psychotherapies is a therapist’s personal interaction with the client”. Likewise, Frank (1974, p. 115) reflected on his time as a patient in two bouts of psychoanalysis and noted “The experiences with analysis …. left me convinced that the relationship with the therapist was much more important than his theory or technique”. Frank (1974, p. 118) “Determinants of the success of psychotherapy of whatever form lie mainly in the patient and, to a lesser degree, in the therapist”. However, the relationship is embedded within the interventions used by the therapist (Beutler and Harwood 2002).

Scholarly papers on psychotherapy have shifted in the style of authorship. Currently, few papers are published by a single author, but instead they reflect the input from a team of collaborators. Furthermore, most current papers are published by researchers with their primary job housed within an academic institution. Fewer papers are being published by full-time clinicians, enlarging the gap between the scientific side of psychotherapy from the realities of clinical practice. The integration of science and practice requires a clear and consistent focus on work that could help to improve the lives of mental health patients (Overholser 2007, 2008). Unfortunately, many faculty members value research over applied work (Overholser 2012), and have become more interested in the brain than the mind (Overholser 2003b).

As the field changes, there are risks that could affect the entire field of psychotherapy. When the majority of articles about psychotherapy have been written by academic researchers who no longer conduct psychotherapy sessions, there is a clear risk that the endorsed treatment strategies will not fit the realities of clinical practice. Not only does this hamper the utility of the published article, but it also derails the effective education of the next generation of psychotherapists. Without ongoing clinical activity, the mental health professional can easily lose touch with the importance of patience, persistence, flexibility, creativity, and sensitivity needed to conduct psychotherapy sessions. As noted by Ellis (1982, p. 25): “efficient therapy remains flexible, curious, empirically-oriented, critical of poor theories and results, and devoted to effective change”. Ellis (1979) encourages an active therapist who vigorously debated the client’s irrational beliefs.

The field of psychotherapy benefits from a sincere bond with the scientist-practitioner model (Overholser 2010, 2012), with faculty members maintaining weekly activity in the direct provision of clinical services (Overholser 2010). It seems essential to encourage the integration theoretical ideas, scientific evidence and clinical applications in psychology (Overholser 2008). Furthermore, it is important for faculty members who teach psychotherapy skills to remain active with their own clinical practice (Overholser 2019). In some situations, the integration of science and practice may be attained through the efforts of a collaborative team or a single individual who remains active in scholarship as well as the direct delivery of clinical services.

Over the years, the field of psychotherapy has seen an expansion of cognitive-behavioral strategies, with a subsequent reduction in articles that focus on experiential, existential, or interpretive approaches. This shift of orientation is aligned with the emphasis on research, as the CBT style is much more closely aligned with research methodology. Even aside from the theoretical orientation comes a shift of basic perspective and clinical focus. Instead of asking “who is this person and how can I be helpful?”, the underlying attitude of many current therapists “What is the problem and how can I fix it?” An accurate diagnosis may help with initial plans for treatment but many other factors are important as well (Wampold et al. 2005). It seems important for the field of psychotherapy to respect its heritage and protect its future by valuing the special bond that develops between therapist and client. As noted by Fine (1974, p. 103), “psychotherapy is a philosophical approach to the problems of living”.