Intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy (ISTDP) is a form of short-term psychotherapy developed through empirical, video-recorded research by Habib Davanloo.[1]

The therapy’s primary goal is to help the patient overcome internal resistance to experiencing true feelings about the present and past which have been warded off because they are either too frightening or too painful. The technique is intensive in that it aims to help the patient experience these warded-off feelings to the maximum degree possible; it is short-term in that it tries to achieve this experience as quickly as possible; it is dynamic because it involves working with unconscious forces and transference feelings.[2][3]

Patients come to therapy because of either symptoms or interpersonal difficulties. Symptoms include traditional psychological problems like anxiety and depression, but they also include physical symptoms without medically identifiable cause, such as headache, shortness of breath, diarrhea, or sudden weakness. The ISTDP model attributes these to the occurrence of distressing situations where painful or forbidden emotions are triggered outside of awareness.[4][5] Within psychiatry, these phenomena are classified as “Somatoform Disorders” in DSM-IV-TR.[6]

The therapy itself was developed during the 1960s to 1990s by Habib Davanloo, a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst from Montreal. He video recorded patient sessions and watched the recordings in minute detail to determine as precisely as possible what sorts of interventions were most effective in overcoming resistance, which he believed was acting to keep painful or frightening feelings out of awareness and prevent interpersonal closeness.[7]

ISTDP is taught by Habib Davanloo at McGill University, as well as in other University and post-graduate settings around the world. The ISTDP Institute offers on-line ISTDP training materials, including introductory videos and skill-building exercises.

Origins and theoretical foundation

[

edit

]

In 1895, Josef Breuer and Sigmund Freud published their Studies on Hysteria, which looked at a series of case studies where patients presented with dramatic neurological symptoms, such as “Anna O” who had headaches, partial paralysis, loss of sensation, and visual disturbances.[8] These symptoms did not conform to known patterns of neurological disease, and neurologists were thus unable to account for symptoms in purely anatomical or physiological terms. Breuer’s breakthrough was the discovery that symptomatic relief could be brought about by encouraging patients to speak freely about emotionally difficult aspects of their lives. Experiencing these emotions which had been previously outside of awareness seemed to be the curative factor. This cure became known as catharsis, and the experiencing of the previously forbidden or painful emotion was abreaction.

Freud tried various techniques to deal with the fact that patients generally seemed resistant to experiencing painful feelings. He moved from hypnosis to free association, interpretation of resistance, and dream interpretation.[9] With each step, therapy became longer. Freud himself was quite open about the possibility that there were many patients for whom analysis could bring little or no relief, and he discusses the factors in his 1937 paper “Analysis Terminable and Interminable.”[10]

From the 1930s through the 1950s, a number of analysts were researching methods of shortening the course of therapy without sacrificing therapeutic effectiveness. These included Sándor Ferenczi, Franz Alexander, Peter Sifneos, David Malan, and Habib Davanloo. One of the first discoveries was that the patients who appeared to benefit most from therapy were those who could rapidly engage, could describe a specific therapeutic focus, and could quickly move to experience their previously warded-off feelings. These also happened to represent those patients who were the healthiest to begin with and therefore had the least need for the therapy being offered. Clinical research revealed that these “rapid responders” were able to recover quickly with therapy because they were the least traumatised and therefore had the smallest burden of repressed emotion, and so were least resistant to experiencing the emotions related to trauma. However, these patients represented only a small minority of those arriving at psychiatric clinics; the vast majority remained unreachable with the newly developing techniques.[11]

A number of psychiatrists began directing their psychotherapeutic research into methods of overcoming resistance. Dr. David Malan popularized a model of resistance, known as the Triangle of Conflict, which had first been proposed by Henry Ezriel.[12] At the bottom of the triangle are the patient’s true, impulse-laden feelings, outside of conscious awareness. When those emotions rise to a certain degree and threaten to break into conscious awareness, they trigger anxiety. The patient manages this anxiety by deploying defences, which lessen anxiety by pushing emotions back into the unconscious.

Triangle of Conflict

The emotions at the bottom of Malan’s Triangle of Conflict originate in the patient’s past, and Malan’s second triangle, the Triangle of Persons, originally proposed by Menninger, explains that old emotions generated from the past are triggered in current relationships and also get triggered in the relationship with the therapist.[13] The question of how maladaptive patterns of interpersonal behaviour could arise from early childhood experiences in the family of origin was postulated within psychoanalytic theory. Independent empirical support came from Bowlby’s newly arising field of Attachment Theory.

Triangle of Persons

Bowlby and attachment trauma

[

edit

]

John Bowlby, a British psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, was very interested in the impact on a child of adverse experiences in relation to its primary attachment figures (usually the mother, but often the father and others) in early life. He concluded, in opposition to received psychoanalytic dogma of the day, that childhood experience was far more important than unconscious fantasy. He also elucidated the nature of attachment, a system of behaviours exhibited by human and other mammalian infants which are innate and have the goal of physical proximity to the mother. For instance, a child taken out of its mother’s arms cries loudly in protest, and it is only quieted by being restored to its mother’s arms. Bowlby observed that the innate attachment system would be activated by loss of proximity to the mother, and that long-lasting trauma to the child could result from attachment interruption. Long term consequences included increased propensity to psychiatric disorders, poor relationship function, and decreased life satisfaction.[14]

Bowlby conducted numerous studies and noted strong correlations between adverse early-life circumstances—primarily the lack of a consistent and nurturing relationship with the mother—as the source of numerous difficulties, including persistent depression, anxiety, or delinquency in adulthood. Childhood traumatisation to the attachment bond, usually through separation from or loss of the primary mother or mother-substitute, led to adult difficulties. Since Bowlby, the effects of trauma over development have consistently been shown to have a significant detrimental impact on adult psychological functioning.[15]

Davanloo’s discovery of the unconscious consequences of attachment trauma

[

edit

]

In the 1960s, while Bowlby was observing children directly, Davanloo was beginning his work with symptomatic and character-disturbed adults. As he began his video-recording work and became progressively successful against higher levels of resistance, he noted that particular themes reappeared with striking consistency in patient after patient.[16]

First, the therapist’s efforts to get to know the patient’s true feelings often aroused a simultaneous mixed feeling in the patient, composed of deep appreciation for the therapist’s relentless efforts to get to know the patient deeply, combined with equally deep irritation at the therapist for challenging the patient to abandon long-held resistances which could thwart the therapeutic effort.

Davanloo noted, in concert with Malan’s Triangle of Conflict, that patients would unconsciously resist the therapist’s efforts to get to the root of their difficulties. He also observed, from his videotaped sessions, that patients would simultaneously send off signals of their unconscious anxiety. Davanloo carefully monitored these signals of anxiety and saw that they represented the rise of complex mixed feelings with the therapist. The mix represented that part of the patient seeking relief from painful symptoms but also an active desire to avoid painful, repressed feelings.

As Davanloo became more skilled at unlocking the patient’s true unconscious feelings, he noted an often very predictable sequence of feelings. The sequence was by no means invariable, but it occurred frequently enough to allow the therapist to hypothesise its existence in a majority of cases.

First, after a high rise of mixed feeling with the therapist, manifested as signals of intense anxiety (tension in skeletal muscle, often manifested as wringing of the hands, accompanied with deep, sighing respirations), there would often be a breakthrough of rage, accompanied by an immediate drop in anxiety. This rage, Davanloo discovered, is intensely felt. It often has a violent impulse associated with it, sometimes even a murderous impulse. Once patients feel this rage, they are able to describe vividly detailed fantasies of what the rage would do if it were to take on a life of its own.

The rage is a product of thwarted efforts to attach from the past. Those thwarted efforts to love and be loved yield pain, in the form of what Bowlby described as protest. The pain yields a reactive rage at the loved person who thwarted attachment efforts.

Complete experiencing of the rageful impulse is typically accompanied by a tremendous relief at finally getting something out which has yearned for release. However, the relief is typically short lived.

Next, Davanloo almost invariably noted that patients then experience a tremendous wave of guilt about the rage. The guilt is a product of the fact that the old rageful feelings were with a person who was also loved. It is this guilt, Davanloo discovered, which is the key ingredient in symptom formation and character difficulties. Symptoms and interpersonal difficulties (usually unconscious efforts to ward off intimacy and closeness) are the product of guilt, which turns the rage back on the self. For instance, the rage of a two-year-old toward a mother who dies may be experienced in the present as suicidal feelings (self-directed murderous rage).

Beneath the guilty feelings from the past, Davanloo almost invariably noted painful feelings about thwarted efforts at emotional closeness to parents and others in childhood. Finally, at the deepest layer of feelings are the still powerful yearnings for closeness, attachment, and love.

The goal of the ISTDP therapist is, as rapidly as possible, to help the patient overcome resistance, and then experience all the waves of mixed, genuine feeling, previously unconscious, triggered by the intense therapeutic process. Those feelings are traced back to their origins in the past, and then both therapist and patient come to understand how the patient came to be the “consciously confused, unconsciously driven” person in the present. Old pockets of emotion are drained, the patient has a clearer self-narrative, and self-destructive symptoms and defences are renounced. The understanding gained is not just cognitive, but goes to the fundamental, emotional core. The influence of Freud’s early trauma theory is evident.

Specific therapeutic interventions

[

edit

]

Davanloo discovered the layers of the dynamic unconscious through a process of developing specific interventions which allow the therapist to reach those layers. Those interventions, applied in a specific fashion at specific times in the therapeutic process, are all calculated to overcome the patient’s resistance as quickly and completely as possible, to allow the earliest and fullest experience of true feelings about the present and past as quickly as possible. Those interventions are known as pressure, challenge, and head-on collision.

I. Pressure: Therapeutic encouragement and reaching through to the patient

[

edit

]

Pressure is the principal ingredient of ISTDP, and it takes many forms. Initially, pressure takes the form of encouraging the patient to describe symptoms and interpersonal difficulties as specifically as possible, so both patient and therapist get the clearest picture possible of the precise difficulties. It starts from the moment the patient walks into the room, in the form of the question, “Are there some difficulties you are experiencing which you would like us to have a look at?”

The primary form of pressure is pressure toward feeling. Again, this is exerted mainly in the form of questions, such as, “How did you feel toward your boss for humiliating you in front of your staff? We see that you got anxious and depressed, but how did you feel?”

Pressure can be toward the patient’s will: “Can we look to your feelings? Do you want us to look to your feelings?”

Pressure is also exerted toward the therapeutic task: “Our goal here, if you want, is to get to the root, the engine, driving your difficulties. So, can we look at a specific time when you experienced anxiety? This will give us a clear picture of the problem which we can use to get to the engine.”

In its essence, pressure is encouragement from the therapist to the patient. It is encouragement to renounce defences, tolerate anxiety, and walk, with the therapist, into those places which have previously been off-limits. It is a way of saying, “There’s nothing in there we cannot face together, and we do so in your service, to relieve you of painful difficulties.”

Patients with low resistance are often quite responsive to pressure alone. However, as explained above, those are the patients who are healthiest to begin with. For patients with higher levels of resistance, usually the product of a more traumatised early phase of life, pressure quickly leads to the patient erecting barriers with the therapist. Those barriers are the patient’s habitual defences against avoided feelings. The combination of intentional (conscious) and unintentional (unconscious) defences is called the resistance. The therapist is constantly monitoring for both the rise in anxiety and the appearance of resistance. When resistance does make its appearance, new interventions, in addition to pressure, are called for.[17]

II. Challenge: Pointing out and interrupting defenses in concert with the patient

[

edit

]

Challenge is a two-stage process. The first stage is clarification, which is the therapist’s effort to confirm that resistance is operating, and also to acquaint the patient with the specific defense being deployed. Patients are often quite unaware of their own defenses. Clarification takes the form of a question, meant to clarify the defense to both patient and therapist: “Do you notice that when you speak of being angry with your boss that you smile and giggle? Is a smile something you sometimes do to cover up a deeper feeling?”

When a defense is properly clarified, both patient and therapist can work together against it, because it represents an obstacle to the therapeutic task of getting to the patient’s true feelings. A defense which has not been clarified is still invisible to the patient. It is also important to note that in childhood, defenses can be a useful tool in emotionally overwhelming or traumatic situations. According to Los Angeles-based psychiatrist Katherine Watkins, M.D. “defenses such as dissociation and repression can shield us from intense feelings that we are developmentally unprepared to experience and process. However as we grow up, this shielding cuts us off from our full range of feelings, even when we are now emotionally able to handle the feelings.”

Challenge to the defenses represents an exhortation to the patient to abandon the defense: “Again you smile when I ask you about feelings in relation to being humiliated by your husband. If you don’t smile, how were you truly feeling?” This particular intervention is a very powerful one in the therapist’s arsenal. As with all powerful interventions, if it is misapplied, the consequences can be severe: rapid misalliance with the therapist, worsening of symptoms, and treatment dropout. This is because the patient perceives a premature challenge, applied when a defense has not been clarified, as a criticism or a personal attack.

A common misunderstanding of ISTDP is that the therapist’s role is to badger the patient through the use of Challenge. However, the proper use of challenge is as an aid or enhancement to the therapeutic alliance by removing an obstacle to the rise in complex feelings with the therapist. If challenge originates as a product of frustration in the therapist or as a misunderstanding of the unconscious, then stalemate is virtually assured.

The main purpose of challenge is to remove any obstacles in the way of the mutually agreed upon task of getting to the engine of the patient’s present difficulties: warded-off, complex feelings in relation to traumatizing experiences with important attachment figures in the past.

The majority of patients are able to experience their true mixed feelings with a combination of Pressure and properly clarified Challenge. However, a sizable minority of patients erect a massive wall of resistance with the therapist. This wall is erected automatically and is an over-learned, habitual response, used to avoid emotional intimacy, both with the therapist and with other important figures in the patient’s personal orbit. When the therapist observes that the patient’s resistance has fully crystallized, it is time to deploy the ultimate intervention.[18]

III. Head-on collision: Pointing out the reality of the defenses and encouragement to overcome them

[

edit

]

The Head-on Collision is an intervention aimed not at any single defense but rather aimed at the entire defensive structure being deployed by the patient. It is an urgent appeal to the patient to exert maximal effort to overcome the resistance, and it takes the form of a summary statement to the patient which explains the consequences of continuing to resist:

Let’s take a look at what’s happening here. You have come on your own free will, because you are experiencing a problem which causes you pain. We have set out to get to the root of your difficulties, but every time we attempt to move toward it, you put up this massive wall. The wall keeps me out, and it keeps you from knowing your own true feelings. If you keep me out, you keep me useless. Is that what you want? Because, as you see, you are certainly capable of keeping me useless to you. My first question is, why would you want me to be useless? You see, the consequences of this would be that I would be unable to help you. I’d like to, but the nature of this work is that I can’t help everyone. Sometimes I fail. However, can you afford to fail? How much longer do you want to carry this burden?

This complex intervention is simultaneously aimed at the patient’s will, is a reminder of the task, and is a wake-up call to the therapeutic alliance to exert maximal effort against the resistance. It is a reminder, in stark terms, that the therapeutic task is in jeopardy and may well fail. Finally, it is a reminder to the patient of the consequences of failure, as well as an implied reminder that success is also possible.[19]

The interventions of Pressure, Challenge, and Head-on Collision, all aimed at helping the patient experience true feelings in relation to the present and past, allowed Davanloo to expand the scope of patients who can be helped by short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy. A model which initially worked only with highly motivated patients able to describe a clearly problematic area can now be applied to patients whose difficulties are diffuse and whose motivation is also initially quite diffuse. The results are deep, lasting changes in areas of both symptomatic and interpersonal disturbances.

It is also worth stressing that ISTDP, unlike traditional psychodynamic therapies, assiduously avoids interpretation until such time as the unconscious is open. The use of trial interpretations is explicitly avoided. The phase of interpretation only commences once it is clear to both therapist and patient that there has been a passage of previously unconscious emotion. Quite often, it is then the patient who takes the lead in interpreting: “The incredible rage I felt toward you when you refused to let me off the hook regarding my feelings is exactly the same rage that I felt toward my father when I was five years old and found out he had been killed in the war and wasn’t coming home. I buried the rage that day because I felt so guilty about it. That’s the day I became depressed.”

Evidence base

[

edit

]

Davanloo’s initial research was published in the form of a qualitative case series of approximately 200 patients. He maintains a large video library of treated cases which he uses for teaching conferences, though this has not yet been made available for other psychotherapy researchers to independently verify and quantify Davanloo’s claims. Recent studies however, support the efficacy of the ISTDP technique, as described below. He claims efficacy with psychological symptoms, medically unexplained symptoms (so-called functional or somatoform disorders), and characterological disturbances (referred to as Personality Disorders in DSM).

Empirical research into the efficacy of ISTDP, and other brief psychodynamic psychotherapies is active. There are now over 60 published outcome studies in ISTDP including 40 randomized controlled trials for depression, anxiety, personality, somatic symptom and substance use disorders. There are also over 20 studies showing the cost effectiveness of the method through reducing doctor visits, medication costs, hospital costs and disability costs. Summary of cost effectiveness studies to 2018

ISTDP has been investigated for:

- Personality Disorders[20][21][22][23][24]

- Depression and Treatment Resistant Depression [25][26][27][28][29][30]

- Anxiety Disorders [31][32][33]

- Functional Neurological Disorders[34][35]

- Somatic Symptom Disorders: at least 20 studies as of October 2019 [36][37][38][39]

[40][full citation needed]

- Cost effectiveness studies: at least 22 studies as of October 2019:[41][42][43][44][32][45][46][47]

- As an Adjunct to Care in Severe Mental Disorders [48][49][47][44][50]

- Substance Use Disorders [51]

A Cochrane systematic review examined the efficacy of short-term psychodynamic psychotherapies for common mental disorders such as depression, anxiety and personality disorders.[52] Without distinguishing between different forms of STDP from Davanloo’s ISTDP, modest to large short-term gains were reported for a broad range of people experiencing common mental disorders.[52] Further research is required to determine the effectiveness and long term benefits of psychodynamic psychotherapies for common mental disorders.[52] Neuroscientist and Nobel Prize winner, Eric Kandel refers to Davanloo’s technique and its effectiveness in providing relief from emotional disturbances.[53]

Relationship to Cognitive Therapy

[

edit

]

Cognitive therapy (CT), developed by Aaron T. Beck, focuses on illogical thoughts as the main driver of emotional difficulties. These beliefs, such as, “Everything I attempt inevitably fails,” are postulated to cause emotional states like depression or hopelessness. The therapist collaborates with the patient to determine which faulty cognitions are currently accepted by the patient as true. Together, the patient and therapist discover these cognitions and collaboratively explore the evidence for and against them. Relief of symptoms comes from replacing unfounded cognitions with more reality-based thoughts. CBT has been shown effective in numerous trials[citation needed], particularly for depression and anxiety disorders[citation needed].

While ISTDP accepts the presence of faulty cognitions, the causality is thought to be reversed. The ISTDP therapist would posit that unconscious emotions lead to unconscious anxiety, which is managed by unconscious defences. These defences can certainly include hopeless, helpless, or self-deprecating cognitions. Rather than examining evidence for and against a thought like, “I am unable to know my own true feelings,” an ISTDP therapist might say, “If you adopt that position, which is essentially a position of helplessness, we will not get to the engine driving your difficulties. If you renounce this helpless position, how are you truly feeling right now?”

Both the CT and ISTDP therapist call the thought into question, with the goal of ultimately liberating the patient. The difference is that the ISTDP therapist sees the faulty cognition as preventing access to the true, buried feelings, while the CT therapist sees the faulty cognition as the cause of the painful emotions leading to the painful psychological state. It may well be the case that causality flows in both directions, dependent on the individual, the emotions, and the cognitions involved. As of this writing, though both CT and ISTDP show good evidence of clinical efficacy, the theoretical question of whether feelings drive thoughts or thoughts drive feelings remains unresolved; it could well be the case that thought and feeling are inextricably bound, and that we have not yet developed adequate psychological or neuroscientific concepts and tools to frame these sorts of questions properly.

References

[

edit

]

Further reading

[

edit

]

- Abbass, Allan. Reaching through Resistance: Advanced Psychotherapy Techniques. Seven Leaves Press, 2015.

- Coughlin Della Selva, Patricia. Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy: Theory and Technique. Karnac, 2004.

- Davanloo, H. Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy. In Kaplan, H. and Sadock, B. (eds), Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, 8th ed, Vol 2, Chapter 30.9, 2628–2652. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

- Davanloo, Habib. Basic Principles and Techniques in Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy. Jason Aronson Publishers, 1994.

- Davanloo, Habib. Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy. Jason Aronson Publishers, 1992.

- Davanloo, Habib. Unlocking the unconscious: Selected papers of Habib Davanloo, MD. New York: Wiley, 1995.

- Davanloo, Habib. Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy: Selected Papers of Habib Davanloo, MD. Wiley, 2000.

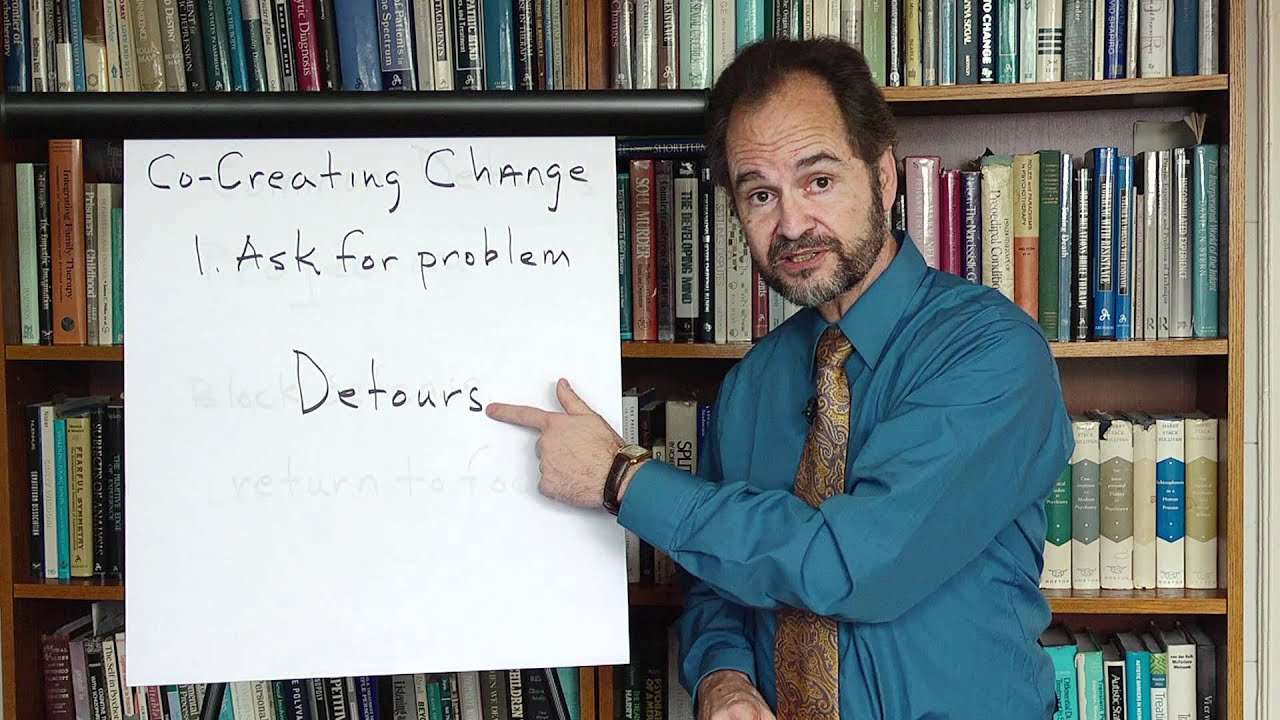

- Frederickson, Jon. Co-Creating Change: Effective Dynamic Therapy Techniques. Seven Leaves Press, 2013.

- Magnavita, Jeffrey. Restructuring Personality Disorders: A Short Term Dynamic Approach. New York: Guilford Press, 1997.

- Malan, David and Coughlin Della Selva, Patricia. Lives Transformed: A Revolutionary Method of Dynamic Psychotherapy. Karnac, 2006.

- Malan, David. Individual Psychotherapy and the Science of Psychodynamics. Oxford University Press, 1995.

- McCullough, Leigh. Treating Affect Phobia: a Manual for Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy. Guilford, 2003.

- McCullough Vaillant, Leigh. Changing Character: Short-Term Anxiety-Regulating Psychotherapy for Restructuring Defenses, Affects, and Attachment. New York: Basic Books, 1997.

- Messer, Stanley and Warren, C. Seth. Models of Brief Psychodynamic Theory: A Comparative Approach. Guilford Press, 1995.

- Sifneos, Peter. Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy: Evaluation and Technique. Springer, 1987.

- Solomon, Marion et al. Short-Term Therapy for Long-Term Change. W.W. Norton and Company, 2001.

- Ten Have-de Labije, Josette and Neborsky, Robert. Mastering Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy: Roadmap to the Unconscious. Karnac, 2012.Winston, A. Clinical and Research Issues in Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy. American Psychiatric Press, 1985.

- Zois, C. and Scarpa M. Short-Term Therapy Techniques. Jason Aronson Press, 1997.