I. BASIC ASSUMPTIONS OF THE IFS MODEL

- It is the nature of the mind to be subdivided into an indeterminate number of subpersonalities or parts.

- Everyone has a Self, and the Self can and should lead the individual’s internal system.

- The non-extreme intention of each part is something positive for the individual. There are no “bad” parts, and the goal of therapy is not to eliminate parts but instead to help them find their non-extreme roles.

- As we develop, our parts develop and form a complex system of interactions among themselves; therefore, systems theory can be applied to the internal system. When the system is reorganized, parts can change rapidly.

- Changes in the internal system will affect changes in the external system and vice versa. The implication of this assumption is that both the internal and external levels of system should be assessed.

II. OVERALL GOALS OF THERAPY

- To achieve balance and harmony within the internal system

- To differentiate and elevate the Self so it can be an effective leader in the system

- When the Self is in the lead, the parts will provide input to the Self but will respect the leadership and ultimate decision making of the Self.

- All parts will exist and lend talents that reflect their non-extreme intentions.

III. PARTS

- Subpersonalities are aspects of our personality that interact internally in sequences and styles that are similar to the ways in which people interact.

- Parts may be experienced in any number of ways — thoughts, feelings, sensations, images, and more.

- All parts want something positive for the individual and will use a variety of strategies to gain influence within the internal system.

- Parts develop a complex system of interactions among themselves. Polarizations develop as parts try to gain influence within the system.

- While experiences affect parts, parts are not created by the experiences. They are always in existence, either as potential or actuality.

- Parts that become extreme are carrying “burdens” — energies that are not inherent in the function of the part and don’t belong to the nature of the part, such as extreme beliefs, emotions, or fantasies. Parts can be helped to “unburden” and return to their natural balance.

- Parts that have lost trust in the leadership of the Self will “blend” with or take over the Self.

IV. SELF

- Different level of entity than the parts — often in the center of the “you” that the parts are talking to or that likes or dislikes, listens to, or shuts out various parts

- When differentiated, the Self is competent, secure, self-assured, relaxed, and able to listen and respond to feedback.

- The Self can and should lead the internal system.

- Various levels of experience of the Self:

- When completely differentiated from all parts (Self alone), people describe a feeling of being “centered.”

- When the individual is “in Self” or when the Self is in the lead while interacting with others (day-to-day experience), the Self is experienced along with the non-extreme aspects of the parts.

- An empowering aspect of the model is that everyone has a Self.

V. GENERAL GROUPS OF PARTS

- EXILES

- Young parts that have experienced trauma and often become isolated from the rest of the system in an effort to protect the individual from feeling the pain, terror, fear, and so on, of these parts

- If exiled, can become increasingly extreme and desperate in an effort to be cared for and tell their story

- Can leave the individual feeling fragile and vulnerable

- MANAGERS

- Parts that run the day-to-day life of the individual

- Attempt to keep the individual in control of every situation and relationship in an effort to protect parts from feeling any hurt or rejection

- Can do this in any number of ways or through a combination of parts — striving, controlling, evaluating, caretaking, terrorizing, and so on.

- FIREFIGHTERS

- Group of parts that react when exiles are activated in an effort to control and extinguish their feelings

- Can do this in any number of ways, including drug or alcohol use, self-mutilation (cutting), binge-eating, sex binges

- Have the same goals as managers (to keep exiles away) but different strategies

VI. BEGINNING TO USE THE MODEL

- Assess client’s parts and sequences around the problem.

- Look for polarizations:

- Within individuals

- Among family members

- Look for parallel dynamics: The way you relate to your own parts parallels the way you relate to those parts of others.

- Introduce the language of the model.

- Check for individual’s awareness of parts — ask how he or she experiences the part: thoughts, feelings, sensations, images, and so on.

- When working with families, check for the family’s awareness of parts in self and others.

- Make a decision about how to begin using the model: language, direct access, imagery, and so on.

- Come to agreement with client on initial goals of therapy in terms of the internal system — create a “contract.”

- Assess the fears of manager parts and value the roles of the managers; explain how the therapy can work without the feared outcomes of the managers happening.

- Inventory dangerous firefighters; work with managers’ fears about triggering firefighters.

- Assess client’s external context and constraints to doing this work.

VII. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL SYSTEMS

- The way you relate to your own parts parallels the way you relate to those parts of others.

- Individual’s internal system affects and is affected by the external system of which he or she is a part.

- Internal and external systems often parallel each other.

VIII. WORKING WITH INDIVIDUALS

- Protective Parts

- Important to assess protective parts and work with them first.

- Develop a direct relationship with the part.

- May need to negotiate pace of work — give the part an opportunity to talk about concerns.

- Work out a system for the part to let you know when things are moving too fast.

- Respect the concerns of the part.

- Non-imaging techniques

- Assessing internal dialogue

- Using the IFS language

- Location/sense of a part in the body

- Diagrams — relationships among parts

- Journaling

- Direct access:

- Therapist to parts

- Self to parts

- Part to part

- Imaging

- Room technique

- Mountain or path exercise

- Going back in time with a part, then “unburdening”

- Bringing parts into the present — “retrieval”

- Future imaging

- Working with more than one part

- Confronting abuse/significant others

- Horizon/healing place

- Use of light

- Concept of Blending: keeping the feelings of the part from overwhelming the Self

- Working with the Self to understand why/how not to blend

- Working with the part to understand why/how not to blend

- Working with young children

- Assess developmental level of child and whether need to be concrete or able to use imaging techniques

- Be creative, use modalities comfortable to child — art, play techniques

- Children respond well to techniques that externalize parts and then involve interacting with the parts, such as sandtray, puppets, and so on.

IX. WORKING WITH FAMILIES

- Introduce IFS language (power of IFS language vs. monolithic language)

- Language is powerful in changing sequences.

- Language frees people from seeing themselves (and others) in extreme ways.

- Looking for parts that are activated in session.

- Identifying sequences (both internal and external)

- Selves working together to keep extreme parts of each family member from interfering

- Enactments

- Set up enactments of family.

- Set up enactments of sequences/relationship among parts of individual family members.

- Work with one family member while others watch.

- Establish safety: Family members not to analyze parts outside of session

- Contract not to talk about others’ parts; can talk about own parts

- No matter what others are doing, individual always responsible for own parts

- Ask for reactions of others who are watching.

- Try to alternate among family members.

- Working with one member outside of family sessions

- Emphasize taking responsibility for own parts and help practice accessing Self.

- General frame of Selves working together to keep extreme parts of each family member from interfering

X. CONSTRAINTS TO THE WORK

- Therapist’s parts (rational/scientific, approval, worrier, protective)

- Protective parts of client

- Protective parts of other family members

- External system unsupportive or abusive

XI. COMMON THERAPIST MISTAKES

- Working with exile before system is ready.

- Therapist assumes he/she is talking to person’s Self when is talking to a part.

- Therapist thinks Self is doing the work, but it’s really a part.

XII. TROUBLESHOOTING PROBLEMS

- Helping Self to distance from/unblend from parts

- Dealing with extreme parts

XIII. STRENGTHS OF THE MODEL

- Focuses on strengths: the undamaged core of the Self, the ability of parts to shift into positive roles

- IFS language provides a way to look at oneself and others differently.

- Language encourages self-disclosure and taking responsibility for behavior.

- IFS language is powerful.

- Provides a way to work with “resistance” and denial

- Ecological understanding of entire therapy system, including therapist

- Respect for individual’s experience of the problem

- Clients provide the material — the therapist doesn’t have to have all the ideas.

- Therapist looks at client’s Self as “co-therapist” and trusts the wisdom of the internal system.

What to Expect at Your First Appointment

Your first appointment with an IFS therapist will likely begin with a review of informed consent and privacy practices, as well as going over any other paperwork the therapist or clinic requires. They may also go over information regarding logistics (e.g. scheduling, cancellation policies) and provide more information about themselves and how they practice therapy. If you have any questions over the information the therapist covers or shares, don’t hesitate to ask.

The rest of the session will primarily be devoted to assessment. The therapist will ask you questions to help them understand what has brought you to therapy. They will also ask what you would like to get out of working together. This is an important part of the therapeutic process because it informs the diagnosis (if applicable) and treatment plan that the therapist will develop. If there is time, the therapist may begin to introduce you to the language and general patterns of an IFS session.

Throughout your first session, you and the therapist will be beginning to build your therapeutic relationship. This will be an ongoing process, and is important to the success of therapy. A good therapeutic relationship is marked by respect, trust, and a sense of safety. Pay attention during your first session to how you feel while talking to the therapist.

Not every client will connect with every therapist and therefore, if you feel a disconnect, it may be wise to continue to meet with other therapists until you find a comfortable fit. The client-therapist relationship is one of the most important predictors of successful therapy outcomes.

If you decide to continue working with the therapist, your next sessions are likely to be focused on beginning to identify and build relationships with your parts. It can take some time to get used to the way IFS works, so don’t worry if it takes a few sessions to get comfortable with the process.

Is Internal Family Systems Therapy Effective?

Internal family systems therapy was designated as an evidence-based treatment in 2015. Although much of the evidence regarding the efficacy of IFS is anecdotal, major research studies are ongoing and will hopefully provide scientific evidence to support what IFS therapists consistently see.

Bessel van der Kolk, a Dutch psychiatrist and one of the leading researchers on trauma, has strongly backed the use of IFS. In his book, The Body Keeps the Score, van der Kolk details his own experience using IFS with clients suffering from traumatic experiences and relationship conflicts.6

Frank Anderson, a psychiatrist and leading mental health professional, has also championed the use of IFS. He is the former chairman/director of the Foundation for Self Leadership, a non-profit working to advance IFS research.

Key Studies

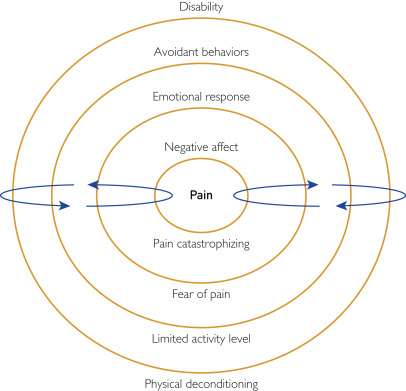

In 2015, the National Registry of Evidence-Based Practices and Programs (NREPP), recognized IFS as an evidence-based psychotherapy model. In their independent, rigorous review NREPP found IFS to be an effective treatment for improving general functioning and well-being in regards to clients with chronic pain. It also found that IFS has promising outcomes for clients experiencing anxiety, depression, issues with self-concept, and physical health conditions.3 While more research is needed, the initial studies suggest that IFS therapy is an effective treatment for a range of mental health conditions and other issues.

The first major study that demonstrated the efficacy of IFS was focused on the use of IFS therapy with patients suffering from rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Published in 2013, it found that individuals suffering from joint pain due to RA experienced a decrease in overall pain and an increase in physical functioning. Those who received IFS therapy also experienced a decrease in self-assessed joint pain, a decrease in depressive symptoms, and an increase in self-compassion. At a one year follow up these results had been maintained.4

In 2017, a study published in the Journal of Marital and Family Therapy demonstrated the effectiveness of IFS therapy in treating depression. The study focused on women in college who had depressive symptoms. It noted that although CBT, interpersonal psychotherapy, and medication are often used to treat this group due to the evidence-based support of these methods, many clients do not improve with these treatment methods. IFS was used as an alternative treatment and was found to help reduce depressive symptoms.2 While promising, additional studies will need to be done.

Risks of IFS

The activation of specific parts in response to trying to access exiled parts may cause an increase in problematic behaviors. It is important to move only as quickly as manager and firefighter parts are comfortable moving.

Other risks of IFS therapy include strong emotional reactions, a worsening of symptoms (usually temporary and common in the beginning of therapy), and lack of progress towards therapeutic goals. These risks are similar to other treatment approaches. Overall, the risks of IFS therapy are not any greater than the risks of other forms of psychotherapy.

Criticisms of IFS

The primary criticism of IFS surrounds the lack of scientific research to support its efficacy. There is substantial anecdotal evidence that supports the use of IFS to treat a range of mental health conditions and other issues. However, additional scientific research is needed to back up those claims. Nevertheless, this criticism may not be important at an individual level provided the therapy yields the relief and positive change the client is seeking.

Critics of IFS also point to the lack of acknowledgement paid to the effects of genetics and biochemistry on mental health. Because IFS takes a fundamentally non-pathologizing stance towards mental health, the use of psychiatric medications are not typically part of an IFS therapist’s recommendation. Mental health professionals who conceptualize mental health disorders as at least partially biochemical in nature are critical of the lack of attention paid to those factors in IFS.

How Is Internal Family Systems Therapy Different Than Other Therapy Options?

IFS is different from other models of psychotherapy in that it emphasizes the natural multiplicity of the mind. It is less solution-focused than most modern psychotherapy models. Instead it focuses on helping clients become more Self-led with the understanding that as Self-leadership increases, disordered thoughts or behaviors naturally decrease.

Many IFS therapists will use an integrative approach, with the IFS model serving as the overarching framework for understanding how healing and growth happens. Through the course of therapy, specific parts of a client may benefit from the integration of techniques from other psychotherapy models.

IFS vs CBT

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is a directive approach that focuses on changing a client’s thoughts in order to change their mood and behavior. It is the most extensively researched model of psychotherapy and can be used to treat a range of mental health disorders. CBT is solution-focused and teaches clients specific techniques to help them address symptoms that negatively impact their functioning.

In comparison to CBT, IFS is a much less directive and solution-focused approach. IFS therapy does not make any effort to change a client’s thoughts or teach skills to do so. Instead, IFS focuses on understanding where the thought is coming from in order to access the wounded parts that have distressing thoughts. In healing those parts, those thoughts naturally change. This causes a cascade effect in which emotions and behaviors are also changed.

IFS vs Person-Centered therapy

Person-centered therapy is a non-directive approach that emphasizes the client’s natural ability to self-actualize, or to grow and change in ways that help them reach their potential. It is a widely used psychotherapy model that tends to work best for clients with anxiety or depression and high motivation to change.

IFS and person-centered therapy are similar in that they both emphasize the client’s expertise in regards to their own life and their innate ability to move towards healing and growth. IFS utilizes concepts very similar to the “core conditions” of person-centered therapy. In person-centered therapy, the therapist creates space for the client to talk while they actively listen. In IFS therapy, the therapist facilitates communication between the client’s Self and their parts.

IFS vs Family Systems Therapy

Although Internal Family Systems Therapy and Family Systems Therapy sound very similar they have a key difference. IFS focuses on the inner workings of a client while Family Systems Therapy focuses on the ways family members interact with and affect one another. IFS therapy was inspired, in part, by Family Systems.

Richard Schwartz, the creator of IFS, was a trained Family Systems therapist. His understanding of how family members interact informed his understanding of a client’s internal parts. While IFS can be used in family therapy, it is more often used in individual therapy.