You’ve almost certainly heard of Sigmund Freud and psychoanalysis, but if you’re like most people, you’re not really sure what psychoanalysis is.

You’ve almost certainly heard of Sigmund Freud and psychoanalysis, but if you’re like most people, you’re not really sure what psychoanalysis is.

You might also wonder how psychoanalysis differs from other forms of talk therapy, and how the theories behind psychoanalysis and other forms of talk therapy differ.

In this piece, we’ll give a brief but comprehensive overview of psychoanalytic theory and practice, the impact of psychoanalysis on other disciplines and areas, and its most common critiques.

So, let’s dive in and learn about Freud, his theories on human behavior and personality (some of which may seem kooky), and his role in the creation and popularization of talk therapy.

Before you read on, we thought you might like to download our 3 Positive Psychology Exercises for free. These science-based exercises will explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology including strengths, values and self-compassion and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students or employees.

What is Psychoanalysis? A Definition and History of Psychoanalytic Theory

Psychoanalysis is a type of therapy that aims to release pent-up or repressed emotions and memories in or to lead the client to catharsis, or healing (McLeod, 2014). In other words, the goal of psychoanalysis is to bring what exists at the unconscious or subconscious level up to consciousness.

This goal is accomplished through talking to another person about the big questions in life, the things that matter, and diving into the complexities that lie beneath the simple-seeming surface.

The Founder of Psychoanalysis: Sigmund Freud and His Concepts

It’s very likely you’ve heard of the influential but controversial founder of psychoanalysis: Sigmund Freud.

Freud was born in Austria and spent most of his childhood and adult life in Vienna (Sigmund Freud Biography, 2017). He entered medical school and trained to become a neurologist, earning a medical degree in 1881.

Soon after his graduation, he set up a private practice and began treating patients with psychological disorders.

His attention was captured by a colleague’s intriguing experience with a patient; the colleague was Dr. Josef Breuer and his patient was the famous “Anna O.,” who suffered from physical symptoms with no apparent physical cause.

Dr. Breuer found that her symptoms abated when he helped her recover memories of traumatic experiences that she had repressed, or hidden from her conscious mind.

This case sparked Freud’s interest in the unconscious mind and spurred the development of some of his most influential ideas.

Models of the Mind

Perhaps the most impactful idea put forth by Freud was his model of the human mind. His model divides the mind into three layers, or regions:

- Conscious: This is where our current thoughts, feelings, and focus live;

- Preconscious (sometimes called the subconscious): This is the home of everything we can recall or retrieve from our memory;

- Unconscious: At the deepest level of our minds resides a repository of the processes that drive our behavior, including primitive and instinctual desires (McLeod, 2013).

Later, Freud posited a more structured model of the mind, one that can coexist with his original ideas about consciousness and unconsciousness.

In this model, there are three metaphorical parts to the mind:

- Id: The id operates at an unconscious level and focuses solely on instinctual drives and desires. Two biological instincts make up the id, according to Freud: eros, or the instinct to survive that drives us to engage in life-sustaining activities, and thanatos, or the death instinct that drives destructive, aggressive, and violent behavior.

- Ego: The ego acts as both a conduit for and a check on the id, working to meet the id’s needs in a socially appropriate way. It is the most tied to reality and begins to develop in infancy;

- Superego: The superego is the portion of the mind in which morality and higher principles reside, encouraging us to act in socially and morally acceptable ways (McLeod, 2013).

The image above offers a context of this “iceberg” model wherein much of our mind exists in the realm of the unconscious impulses and drives.

If you’ve ever read the book “Lord of the Flies” by William Golding, then you have enjoyed the allegory of Freud’s mind as personified by Jack as the Id, Piggy as the ego, and Ralph as the superego.

Defense Mechanisms

Freud believed these three parts of the mind are in constant conflict because each part has a different primary goal. Sometimes, when the conflict is too much for a person to handle, his or her ego may engage in one or many defense mechanisms to protect the individual.

These defense mechanisms include:

- Repression: The ego pushes disturbing or threatening thoughts out of one’s consciousness;

- Denial: The ego blocks upsetting or overwhelming experiences from awareness, causing the individual to refuse to acknowledge or believe what is happening;

- Projection: The ego attempts to solve discomfort by attributing the individual’s unacceptable thoughts, feelings, and motives to another person;

- Displacement: The individual satisfies an impulse by acting on a substitute object or person in a socially unacceptable way (e.g., releasing frustration directed toward your boss on your spouse instead);

- Regression: As a defense mechanism, the individual moves backward in development in order to cope with stress (e.g., an overwhelmed adult acting like a child);

- Sublimation: Similar to displacement, this defense mechanism involves satisfying an impulse by acting on a substitute but in a socially acceptable way (e.g., channeling energy into work or a constructive hobby) (McLeod, 2013).

The 5 Psychosexual Stages of Development

Finally, one of the most enduring concepts associated with Freud is his psychosexual stages. Freud proposed that children develop in five distinct stages, each focused on a different source of pleasure:

- First Stage: Oral—the child seeks pleasure from the mouth (e.g., sucking);

- Second Stage: Anal—the child seeks pleasure from the anus (e.g., withholding and expelling feces);

- Third Stage: Phallic—the child seeks pleasure from the penis or clitoris (e.g., masturbation);

- Fourth Stage: Latent—the child has little or no sexual motivation;

- Fifth Stage: Genital—the child seeks pleasure from the penis or vagina (e.g., sexual intercourse; McLeod, 2013).

Freud hypothesized that an individual must successfully complete each stage to become a psychologically healthy adult with a fully formed ego and superego. Otherwise, individuals may become stuck or “fixated” in a particular stage, causing emotional and behavioral problems in adulthood (McLeod, 2013).

The Interpretation of Dreams

Another well-known concept from Freud was his belief in the significance of dreams. He believed that analyzing one’s dreams can give valuable insight into the unconscious mind.

In 1900, Freud published the book The Interpretation of Dreams in which he outlined his hypothesis that the primary purpose of dreams was to provide individuals with wish fulfillment, allowing them to work through some of their repressed issues in a situation free from consciousness and the constraints of reality (Sigmund Freud Biography, n.d.).

In this book, he also distinguished between the manifest content (the actual dream) and the latent content (the true or hidden meaning behind the dream).

The purpose of dreams is to translate forbidden wishes and taboo desires into a non-threatening form through condensation (the joining of two or more ideas), displacement (transformation of the person or object we are concerned about into something or someone else), and secondary elaboration (the unconscious process of turning the wish-fulfillment images or events into a logical narrative) (McLeod, 2013).

Freud’s ideas about dreams were game-changing. Before Freud, dreams were considered insignificant and insensible ramblings of the mind at rest. His book provoked a new level of interest in dreams, an interest that continues to this day.

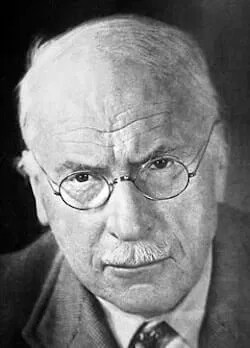

Jungian Psychology: Carl Jung

Freud’s work was continued, although in altered form, by his student Carl Jung, whose particular brand of psychology is known as analytical psychology. Jung’s work formed the basis for most modern psychological theories and concepts.

Jung and Freud shared an interest in the unconscious and worked together in their early days, but a few key disagreements ended their partnership and allowed Jung to fully devote his attention to his new psychoanalytic theory.

The three main differences between Freudian psychology and Jungian (or analytical) psychology are related to:

- Nature and Purpose of the Libido: Jung saw libido as a general source of psychic energy that motivated a wide range of human behaviors—from sex to spirituality to creativity—while Freud saw it as psychic energy that drives only sexual gratification;

- Nature of the Unconscious: While Freud viewed the unconscious as a storehouse for an individual’s socially unacceptable repressed desires, Jung believed it was more of a storehouse for the individual’s repressed memories and what he called the collective or transpersonal unconscious (a level of unconscious shared with other humans that is made up of latent memories from our ancestors);

- Causes of Behavior: Freud saw our behavior as being caused solely by past experiences, most notably those from childhood, while Jung believed our future aspirations have a significant impact on our behavior as well (McLeod, 2014).

Lacanian Psychoanalysis: Jacques Lacan

In the mid to late 1900s, the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan called for a return to Freud’s work, but with a renewed focus on the unconscious and greater attention paid to language.

Lacan drew heavily from his knowledge of linguistics and believed that language was a much more important piece of the developmental puzzle than Freud assumed.

There are three key concepts of Lacanian psychoanalysis that set it apart from Freud’s original talk therapy:

- The Real;

- Symbolic Order;

- Mirror Stage.

The Real

While Freud saw the symbolic as being indicative of a person’s unconscious mind, particularly in dreams, Lacan theorized that “the real” is actually the most foundational level of the human mind. According to Lacan, we exist in “the real” and experience anxiety because we cannot control it.

Unlike the symbolic, which Freud proposed could be accessed through psychoanalysis, the real cannot be accessed. Once we learn and understand language, we are severed completely from the real. He describes it as the state of nature, in which there exists nothing but a need for food, sex, safety, etc. (The Real, 2002).

Symbolic Order

Lacan’s symbolic order is one of three orders that concepts, ideas, thoughts, and feelings can be placed into. Our desires and emotions live in the symbolic order, and this is where they are interpreted, if possible. Concepts like death and absence may be integrated into the symbolic order because we have at least some sense of understanding of them, but they may not be interpreted fully.

Once we learn a language, we move from the real to the symbolic order and are unable to move back to the real. The real and the symbolic are two of the three orders that live in tension with one another, the third being the imaginary order (Symbolic Order, 2002).

Mirror Stage

Lacan proposed that there is an important stage of development not covered by Freud called the “mirror stage.” This aptly named stage is initiated when infants look into a mirror at their own image. Most infants become fascinated with the image they see in the mirror, and may even try to interact with it.

But eventually, they realize that the image they are seeing is of themselves.

Once they realize this key fact, they incorporate what they see into their sense of “I,” or sense of self. At this young stage, the image they see may not correspond to their inner understanding of their physical self, in which case the image becomes an ideal that they strive for as they develop (Hewitson, 2010).

The Approach: Psychoanalytic Perspective

In the psychoanalytic approach, the focus is on the unconscious mind rather than the conscious mind. It is built on the foundational idea that your behavior is determined by experiences from your past that are lodged in your unconscious mind.

While the focus on sex has lessened over the decades since psychoanalysis was founded, psychology and talk therapy still place a big emphasis on one’s early childhood experiences (Psychoanalytic Perspective, n.d.).

Methods and Techniques

A psychoanalyst can use many different techniques, but there are four basic components that comprise modern psychoanalysis:

- Interpretation;

- Transference analysis;

- Technical neutrality;

- Countertransference analysis.

1. Interpretation

Interpretation is the verbal communication between analysts and clients in which analysts discuss their hypotheses of their clients’ unconscious conflicts.

Generally, analysts will help clients see the defensive mechanisms they are using and the context of the defensive mechanisms, or the impulsive relationship against which the mechanism was developed, and finally the client’s motivation for this mechanism (Kernberg, 2016).

There are three classifications of interpretation:

- Clarification, in which the analyst attempts to clarify what is going on in the patient’s consciousness;

- Confrontation, which is bringing nonverbal aspects of the client’s behavior into his or her awareness;

- Interpretation proper, which refers to the analyst’s proposed hypothesis of the unconscious meaning that relates all the aspects of the client’s communication with one another (Kernberg, 2016).

2. Transference Analysis

Transference is the term for the unconscious repetition in the “here and now” of conflicts from the client’s past. Transference analysis refers to “the systematic analysis of the transference implications of the patient’s total verbal and nonverbal manifestations in the hours as well as the c patient’s direct and implicit communicative efforts to influence the analyst in a certain direction” (Kernberg, 2016).

This analysis of the patient’s transference is an essential component of psychoanalysis and is the main driver of change in treatment.

In transference analysis, the analyst takes note of all communication, both verbal and nonverbal, the client engages in and puts together a theory on what led to the defensive mechanisms he or she displays. That theory forms the basis for any attempts to change the behavior or character of the client.

3. Technical Neutrality

Another vital piece of psychoanalysis is what is known as technical neutrality, or the commitment of the analyst to remain neutral and avoid taking sides in the client’s internal conflicts; the analyst strives to remain at an equal distance from the client’s id, ego, and superego, and from the client’s external reality.

Additionally, technical neutrality demands that the analyst refrains from imposing his or her value systems upon the client (Kernberg, 2016).

Technical neutrality is sometimes considered indifference or disinterest in the client, but that is not the goal; rather, analysts aim to serve as a mirror for their clients, reflecting clients’ own characteristics, assumptions, and behaviors back at them to aid in their understanding of themselves.

4. Countertransference Analysis

This final key component of psychoanalysis is the analysis of countertransference, the analyst’s reactions to clients and the material they present in sessions. According to Kernberg:

“contemporary view of countertransference is that of a complex formation codetermined by the analyst’s reaction to the patient’s transference, to the reality of the patient’s life, to the reality of the analyst’s life, and to specific transference dispositions activated in the analyst as a reaction to the patient and his/her material”

(2016).

Countertransference analysis can be generally understood as the analyst’s attempts to analyze their own reactions to the client, whatever form they take.

To engage in psychoanalytic treatment, the analyst must see the client objectively and understand the transference happening in the client and in their own experience.

Transference and Other Forms of Resistance in Psychoanalysis

Speaking of transference, it is one of the many forms of resistance considered in psychoanalysis. In psychoanalytic theory, resistance has a specific meaning: the blocking of memories from consciousness by the client (Fournier, 2018).

Resistance is the client’s general unwillingness to change their behavior and engage in growth through therapy. This resistance can develop by myriad reasons, some conscious and some unconscious, and can even be present in those who want to change.

Transference occurs when clients redirect their emotions and feelings from one person to another, often unconsciously, and represents a resistance or obstacle between clients and their desired states (healing).

It frequently occurs in treatment in the form of transference onto the therapist, in which the client applies their feelings and expectations toward another person onto the therapist.

There are many different types of transference, but the most common include:

- Paternal transference: In this type, the client looks to another person as a father or idealized father figure (e.g., wise, authoritative, powerful);

- Maternal transference: The client looks to another person as a mother or an idealized mother figure (e.g., comforting, loving, nurturing);

- Sibling transference: This type may occur when parental relationships break down or are lacking; instead of treating another person as a parent (in a leader/follower type relationship), the client transfers a more peer-based relationship onto the other person;

- Non-familial transference: This is a more general type of transference in which the client treats others as idealized versions of what the client expects them to be, rather than what they truly are; this type of transference can lead the client to form stereotypes (Good Therapy, 2015).

Transference is not necessarily harmful but may be a form of client resistance to treatment. If the client is projecting inappropriate or unrealistic expectations onto the therapist, he or she may not be entirely open to the change that treatment can provoke.

Resistance to treatment can also be understood in a more general, non-psychoanalytic manner. After all, resistance to treatment is not an uncommon occurrence.

Examples of ways in which a client may resist change in treatment include:

- Silence or minimal discussion with the therapist;

- Wordiness or verbosity;

- Preoccupation with symptoms;

- Irrelevant small talk;

- Preoccupation with the past or future;

- Focusing on the therapist or asking the therapist personal questions;

- Discounting or second-guessing the therapist;

- Seductiveness;

- False promises or forgetting to do what is agreed upon;

- Not keeping appointments;

- Failing to pay for appointments (Lavoie, n.d.).

On the Couch: Why You Lie Down During Treatment

Although it has frequently been used in satire and cartoons to poke fun at psychoanalysis, there are some good reasons why the couch is an important aspect of the psychoanalytic treatment experience.

Dr. Harvey Schwartz explains that having the client lie on the couch instead of sitting face-to-face with the analyst frees both participants from the social constraints established by looking at one another:

“Both have the opportunity to let their minds run free in relation to each other. The unconscious communication that can result fosters a more profound intimacy and deeper self-discovery”

(2017).

Further, Schwartz notes these important points regarding the couch:

- It is used when the client is ready, and there is no pressure to use it;

- There is no “right” way to use the couch—each client’s experience is unique;

- The couch can facilitate greater levels of honesty that aid in the treatment process;

- It can facilitate self-acceptance and reduce inhibitions;

- The couch can be considered a place of freedom, in which you can explore the deeper aspects of your pains and your passions (2017).

While the couch isn’t necessary for patients in psychoanalysis, it is recommended and encouraged for optimal results.

Psychoanalysis Test: The Freudian Personality Test

If you’re interested in taking a quick and easy test to determine whether you are stuck, or fixated, at a stage of development, you can find one here. It presents 21 items that may or may not describe your personality, and you decide how well it describes you, generally on a scale from Very Inaccurate to Very Accurate.

Although you will need to visit a psychoanalyst if you want a more valid and reliable diagnosis, this test can give you an idea of where your personality lies. However, please note that you will need to make an account with Psychologist World to obtain your results.

For a test with free access to your results, check out this Freudian Personality Style Test from the Individual Differences Research Labs. This test is composed of 48 items rated on a 5-point scale from Disagree to Agree. Your results are in the form of scores ranging from 0% to 100% on eight personality styles:

- Oral-Receptive;

- Oral-Aggressive;

- Anal-Expulsive;

- Anal-Retentive;

- Phallic-Aggressive;

- Phallic-Compensative;

- Classic Hysteric;

- Retentive Hysteric.

You can find this test here.

Psychodynamic vs. Psychoanalytic Theory

With all of the theories and disciplines sporting the “psycho” prefix, it’s easy to get them confused.

Psychodynamic theory and psychoanalytic theory have quite a bit in common; in fact, psychoanalytic theory is a sub-theory of psychodynamic theory. “Psychodynamic” refers to all psychological theories of human functioning and personality and can be traced back to Freud’s original formulation of psychoanalysis.

By contrast, psychoanalytic theory refers exclusively to Freud’s psychoanalytic theory.

Given the relationship between the two theories, there are several core ideas and assumptions that they have in common, including:

- The significance of internal drives;

- The impact of the unconscious on human personality and behavior;

- Human thoughts, feelings, and behaviors as being rooted in our earliest experiences;

- All behavior as being determined by internal factors (i.e., it is never random and behavior cannot be completely controlled by the individual) (McLeod, 2017).

Psychoanalysis vs. Psychotherapy

So, given the difference between the two “psycho-” theories above, what is the difference between psychoanalysis and psychotherapy?

The main distinctions between psychoanalysis and psychotherapy lie in both the goals of the treatment and the methods used to achieve those goals.

Psychotherapy is a type of “talk therapy” that is offered as a treatment for a wide range of ailments and mental disorders. The goal is to solve a problem and/or address symptoms that are affecting the client’s quality of life, and there are many ways to go about working to reach this goal.

Those methods vary depending on the type of psychotherapy in question. Some of the most common types include:

Psychoanalysis also falls within this list of common types of psychotherapy, but it has a more specific goal: helping the client (or patient) overcome the desires and negative influences of his or her unconscious mind.

The techniques used in psychoanalysis differ from most other types of psychotherapy, demonstrated by the stereotypical image of psychoanalysis of the client reclining on a couch facing away from the therapist (or analyst) while discussing his or her past.

Psychotherapy can be undertaken with a variety of length and duration combinations, from once a month to several times a week. On the other hand, psychoanalysis is almost always applied in an intensive manner, often requiring three to five sessions a week for several years (Lee, 2010).

A Psychoanalyst vs. a Psychotherapist: Is There a difference?

In case the descriptions above didn’t make it clear, there is certainly a difference between a psychoanalyst and a psychotherapist.

A psychoanalyst has a particular set of skills gained from specific psychoanalysis training.

While psychotherapists may practice multiple types of therapy (although they often specialize in a certain type of therapy or in treating a particular mental health issue), psychoanalysts generally stick to practicing only psychoanalysis.

However, the two professions both focus on helping people via talk therapy, and both use their skills to help their clients gain insight about themselves, address their mental and emotional issues, and heal.

In fact, a psychoanalyst is often considered to be a type of psychotherapist, just one who specializes in psychoanalysis. With that in mind, every psychoanalyst is also a psychotherapist, but not every psychotherapist is a psychoanalyst.

Popular Books on Psychoanalysis

Psychoanalysis has been around for more than 100 years and has generated plenty of debate—much of it heated. Unsurprisingly, given how long it has been practiced, there are many, many books available on the subject.

Some of the most popular and well-reviewed books on psychoanalysis are listed here:

- Psychoanalysis: A Very Short Introduction by Daniel Pick (Amazon);

- Psychoanalysis: The Impossible Profession by Janet Malcolm (Amazon);

- Psychoanalytic Perspectives on Developmental Psychology by Joseph M. Masling and Robert F. Bornstein (link);

- Practical Psychoanalysis for Therapists and Patients by Owen Renik (Amazon);

- Psychoanalysis and Psychoanalytic Therapies (Theories of Psychotherapy) by Jeremy D. Safran (Amazon);

- The How-To Book for Students of Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy by Sheldon Bach (Amazon).

Psychoanalysis in Art and Literature

Due to psychoanalysis’s tenure as an influential theory and form of therapy, it’s had a sizable presence in art, literature, and films. If self-help books tend not to thrill you, you might find some interesting works on psychoanalysis in other places.

For a fascinating look at how art has been influenced by psychoanalysis, check out Laurie Schneider Adams’s book Art and Psychoanalysis. For a briefer look at the interaction between the two, you can find a good, concise overview through Ivy Roberts’s online lesson titled “The Impact of Psychoanalysis on Art.”

Psychoanalysis has also left its mark on literature, both by inspiring works of fiction that incorporate aspects of psychoanalysis and/or psychoanalytic theory and by serving as the basis for psychoanalytic literary criticism, in which literature is critiqued through the lens of psychoanalytic theory.

For a brief overview of the effects of psychoanalysis on literature, check out Susan van Zyl’s article “Psychoanalysis and Literature: An Introduction” by clicking here.

At the Movies: 15 Films Influenced by Psychoanalysis

The impact of psychoanalysis on movies is perhaps even more salient than its impact on art and literature. The list below is just a sampling of the many films inspired and/or influenced by psychoanalysis:

- Sisters (1973) directed by Brian de Palma;

- Un Chien Andalou (1928) directed by Luis Buñuel;

- A Dangerous Method (2011) directed by David Cronenberg;

- The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (1974) directed by Werner Herzog;

- The Piano Teacher (2001) directed by Michael Haneke;

- Dogtooth (2009) directed by Yorgos Lanthimos;

- Blue Velvet (1986) directed by David Lynch;

- Black Swan (2010) directed by Darren Aronofsky;

- Shame (2011) directed by Steve McQueen;

- A Clockwork Orange (1971) directed by Stanley Kubrick;

- Psycho (1960) directed by Alfred Hitchcock;

- Fight Club (1999) directed by David Fincher;

- Antichrist (2009) directed by Lars van Trier;

- My Winnipeg (2007) directed by Guy Madden;

- Another Woman (1988) directed by Woody Allen.

To read more about how psychoanalysis ties into each of these movies, see Bryan Norton’s article on the subject here.

Criticisms of Psychoanalytic Therapy

Although psychoanalytic theory laid the foundations for much of modern psychology, it is not without its flaws. Psychoanalysis is still practiced today, and psychoanalytic theory has been updated to fall more in line with current knowledge about human behavior and the brain, but there are many criticisms of the theory and its applications.

The major criticisms are:

- Many of the hypotheses or assumptions of psychoanalytic theory cannot be tested by empirical means, making it nearly impossible to falsify or confirm;

- It overemphasizes the deterministic roles of biology and the unconscious, leaving little room for influence from the conscious mind;

- Psychoanalytic theory was deeply rooted in Freud’s sexist ideas, and traces of this sexism still remain in the theory and practice today;

- It has generally not been supported across cultures, and may actually apply only to Western culture;

- Freud may have relied too much on a pathology framework, seeing behaviors as inappropriate and/or harmful when they might be inherent to the normal human experience;

- The theory was not developed through the application of the scientific method but from (likely highly subjective) personal reports from Freud on his experience with clients;

- There is little evidence of many of Freud’s theories, including the repression of childhood sexual abuse and trauma.

Given these many valid criticisms of psychoanalytic theory, it is probably wise to approach Freud and his theories with a grain of salt. Although his work formed the basis for modern psychology, that basis was lacking in empiricism and falsifiability, and his students and followers bore the larger burden of providing evidence to back the resulting psychological theories.

A Take-Home Message

Even though psychoanalysis is less prevalent in the treatment of mental health issues today than it was in the early 1900s, it is important to learn about the theories since they had a giant and lasting impact on the field of psychology.

Sigmund Freud is not valued today as a top-notch employer of scientifically-backed methods, and for good reason; however, his work does provide key insight.

What do you think about psychoanalysis and the theory behind it? Does any of it ring true for you personally? Have you ever tried psychoanalysis, as a patient or as an analyst?

We want to hear about your experiences. Leave us a comment and weigh in on this controversial topic.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our 3 Positive Psychology Exercises for free.

References

- Fournier, G. (2018). Resistance. Psych Central. Retrieved from https://psychcentral.com/encyclopedia/resistance/

- Good Therapy. (2015). Transference. GoodTherapy PsychPedia. Retrieved from https://www.goodtherapy.org/blog/psychpedia/transference

- Hewitson, O. (2010). What does Lacan say about… The mirror stage? – Part 1. Lacan Online. Retrieved from http://www.lacanonline.com/index/2010/09/what-does-lacan-say-about-the-mirror-stage-part-i/

- Kernberg, O. (2016). The four basic components of psychoanalytic technique and derived psychoanalytic psychotherapies. World Psychiatry, 15, 287-288.

- Lavoie, S. (n.d.). Resistance in psychotherapy: Definition & concept. Introduction to Psychology: Homework Help Resource. Retrieved from https://study.com/academy/lesson/resistance-in-psychotherapy-definition-lesson-quiz.html

- Lee, J. (2010). The difference between psychotherapy and psychoanalysis. Choose Help. Retrieved from https://www.choosehelp.com/topics/counseling/the-difference-between-psychotherapy-and-psychoanalysis

- McLeod, S. (2014). Carl Jung. Simply Psychology. Retrieved from https://www.simplypsychology.org/carl-jung.html

- McLeod, S. (2014). Psychodynamic approach. Simply Psychology. Retrieved from https://www.simplypsychology.org/psychodynamic.html

- Psychoanalytic Perspective (Psychoanalytic Approach). (n.d.). In Alleydog.com’s online glossary. Retrieved from https://www.alleydog.com/glossary/definition-cit.php?term=Psychoanalytic+Perspective+%28Psychoanalytic+Approach%29

- Schwartz, H. (2017). People don’t still lie on a couch, do they? Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/psychoanalysis-unplugged/201710/people-don-t-still-lie-couch-do-they

- Sigmund Freud Biography. (2018). In A&E Television Network’s The Biography.com website. Retrieved from https://www.biography.com/people/sigmund-freud-9302400

- Symbolic Order. (2002). Purdue’s Introductory Guide to Critical Theory. Retrieved from https://www.cla.purdue.edu/english/theory/psychoanalysis/definitions/symbolicorder.html

- The Real. (2002). Purdue’s Introductory Guide to Critical Theory. Retrieved from https://www.cla.purdue.edu/english/theory/psychoanalysis/definitions/real.html