If you’re like most college students, chances are you experience some school-related stress from time to time. Stress isn’t always a bad thing. In fact, it’s necessary and healthy, but only at manageable levels. Stress pushes us to stay on track with our studying and classwork and keeps us motivated. But when stress, worry, and anxiety start to overwhelm us, it makes it harder to focus and get things done. In fact, national studies of college students have repeatedly found that emotional health challenges like stress, anxiety, sleep and depression are the leading impediments to academic success. And while we might jump from assignment to assignment in an effort to try and get things done quickly, this approach often means we aren’t really finishing anything or finding the focus we need to be effective. In other words, we’re just spinning our wheels and creating more stress.

If you or someone you know is exhibiting dangerous levels of stress, text “START” to 741-741 or call 1-800-273-TALK (8255)

How Does Academic Stress Hurt Us?

It’s understandable to feel stress in college. Maybe you’re on a scholarship and you need to maintain certain grades to stay eligible. Maybe you’re the first person in your family to attend college and you feel pressure to fulfill the weight of those expectations. Maybe you know that college is a financial burden on your family and you worry that your education won’t be worth it or that the burden will be too much. These are all normal feelings and most importantly, not uncommon. You aren’t alone.

Research indicates that when we feel overwhelming stress related to school it not only demotivates us to do the work, it reduces our overall academic achievement and can lead to increased dropout rates. Not to mention the negative health implications, including depression, poor sleep, substance abuse, and anxiety. How this translates in the longer term can affect our ability to sustain employment and decrease our earning potential over a lifetime. But, there’s hope and moreover, help. Figuring out how to manage your stress starts with being able to recognize it.

How Do We Recognize Too Much Stress?

As we said earlier, some stress is good. It’s what pushes us to do the work and meet our deadlines. But when that stress takes over and actually results in less productivity — not more — then it’s time to take action. Here are some ways to recognize if we or someone we know is suffering from too much stress:

Find the source of stress:

- Is it a particular class or type of work?

- Is it an issue of time management and prioritization?

- Do you have too much on your plate?

- Is it due to family expectations or financial obligations?

Pinpoint how that stress is affecting you:

- Is the stress preventing you from sleeping?

- Is it making you take longer to do the work or paralyzing you from even starting?

- Is it causing you to feel anxious, unwell, or depressed?

Because stress seems like it should be typical, too often we dismiss it and get down on ourselves for feeling like there’s something wrong with us and we should be handling it better. It’s important to remember that we’re not alone.

Common Signs that Someone Might Need More Support

It’s important to be able to recognize when stress starts to become all encompassing, affecting our overall mental health and well-being. Here are some signs we might need to get help:

- Insomnia or chronic trouble sleeping

- Inability to motivate

- Anxiety that results in physical symptoms (hair loss, nail biting, losing weight)

- Depression (not wanting to spend time with friends, making excuses, sleeping excessively)

- Mood swings (bursting into tears, bouts of anger)

Remember, support and help are available. Stress doesn’t have to get the best of you. JED has resources at your fingertips and support is a call or text away if you need help urgently:

- Text “START” to 741-741

- Call 1-800-273-TALK (8255)

If academic stress is becoming a struggle, check out this article with tips on how to manage school stress.

Emotionally arousing events are typically very well-remembered. Likewise, individuals who experienced extremely stressful (traumatic) events may suffer from very vivid memories of these events, suggesting that severe stress during or just before encoding may boost memory formation. In line with these observations, studies showed that also lower levels of stress (as they may occur more frequently in schools) during or just before learning may strengthen human memory.20–23 This effect of stress on encoding was often stronger for emotional compared with neutral learning material.24 Another factor moderating the influence of stress on learning is the correspondence between the stressful context and the learning material. For example, stress during learning specifically enhanced memory for material that was related to the context of the stressful task and thus putatively more relevant.20 Material that is unrelated to an ongoing stressor, however, is typically not very well-remembered later on.25 Despite many studies showing a stress-induced learning enhancement if stressor and learning coincide, some studies found the opposite effect.26,27 This divergence might be due to other factors than just the timing of the stressful encounter, such as differences in the interval between study and retrieval or individual differences due to sex, genetics or the developmental background.28–31 In sum, being moderately stressed can enhance memory formation for emotional material and information that is related to the stressful context, whereas stress may impair the encoding of stressor-unrelated material.

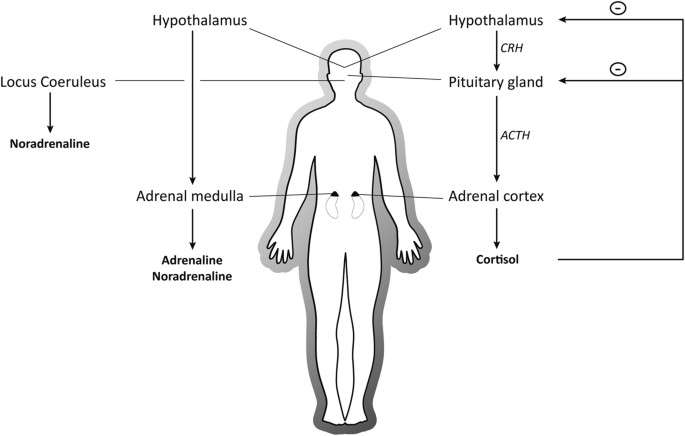

At the neural level, catecholamines such as NA appear to play a critical role in the enhancing effects of stress or emotional arousal on learning. Studies in rodents demonstrated that NA exposure strengthened synaptic contacts in the hippocampus11 and that the concentration of NA in the amygdala after encoding predicted memory strength.32 Corticosteroids, however, appear to play an important role as well. For instance, MR-activation rapidly enhanced neural excitability in the amygdala and hippocampus which may further aid successful memory encoding.15,16 Additional evidence for a role of corticosteroids came from human pharmacological studies, demonstrating that the administration of 20 mg cortisol prior to learning boosted later memory, especially for emotionally arousing pictures.33 Notably, this memory advantage for emotional material depends on NA, as it can be blocked by the beta-blocker propranolol.34 Human neuroimaging studies then set out to elucidate the neural mechanism underlying the stress-induced learning enhancement. The immediate release of NA under stress activated a network of brain regions known as the salience network encompassing the amygdala, anterior cingulate cortex and anterior insula.35,36 This rapid upregulation of the salience network allowed enhanced vigilance and better processing of threat-related information which may improve memory encoding in stressful situations. Some minutes later, the release of cortisol reduced global signal in the electroencephalogram (EEG), which was interpreted as a reduction in background processing in order to allow efficient processing of relevant information by enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio.37 In line with an enhanced processing of important information, the stress-induced increase in processing and encoding of study items in the brain was related to better memory performance for these items at test.38,39 Several studies also investigated the interplay of NA and cortisol in memory encoding. Supporting evidence for such an interaction came, for instance, from a study showing that emotional learning material activated the amygdala, an effect that depended on NA availability as it was abolished by propranolol.40 Importantly, this amygdala response to emotional stimuli was particularly prominent in those individuals with higher cortisol levels during encoding.41 Moreover, the combined administration of cortisol and yohimbine, a drug increasing NA stimulation, switched neural activity towards a strong deactivation of prefrontal areas,42 potentially releasing the amygdala from inhibitory top-down control and improving memory encoding.

While stress around the time of learning enhances memory, stress (or cortisol administration of 25 mg) long before learning or in a distinctly different context does not promote new learning43 and can even hinder successful encoding of new information.21 For example, while stress directly before learning enhanced later recognition memory, memory was impaired if stress was experienced 30 min before learning.21 This memory impairing effect of stress long before learning has been associated with a decrease in neural excitability in the hippocampus long after cortisol administration,44 which might suggest that genomic actions of cortisol protect the consolidation of information learned during the stressful encounter.2 In line with this finding of decreased hippocampal excitability, cortisol administered more than 1 h before MRI measurements reduced hippocampal and amygdala activity in humans,45,46 possibly impairing the formation of new memories. In the same time period, the activity of the salience network decreased again to pre-stress levels while activity in the executive control network increased,35 allowing the individual to recover from the stressful situation and to re-approach homoeostasis. However, there is evidence that this reversal of heightened salience network activity, which is important for higher cognitive control functions to improve coping in the aftermath of stress, does not occur when the participants remain in the stressful context. For instance, the coupling between the amygdala and the salience network remained enhanced after 1 h if the participants were still in the context of the stress induction procedure,47 again highlighting the role of context as a moderator of stress effects on learning.

When stress is experienced before or during a learning episode, its effects on memory encoding can hardly be dissociated from those on memory consolidation. Also in educational settings, influences of stress on memory encoding can often not be separated from those on memory storage. However, by administering stress or stress mediators shortly after learning, thus excluding an influence on memory encoding, experimental studies were able to isolate stress effects on memory consolidation. Several studies in humans showed that stress or adrenaline injections shortly after learning improved memory consolidation, an effect which was more pronounced for emotionally arousing material,26,48, 49, 50 highlighting the importance of the emotionality of the study material. Studies in rodents also demonstrated that the administration of NA or corticosteroids just after learning improved consolidation,51 and that this enhancing effect (at least on hippocampal memory) required the interaction between NA and GR-mediated cortisol effects in the amygdala.52–55

The effects of stress on memory are, however, not limited to the formation of memories (i.e., memory encoding and consolidation) but extend also to memory retrieval. Given that exams and tests can easily cause stress in students and students are evaluated based on their performance in these tests, it is particularly relevant to understand how stress affects memory recall. In line with seminal findings in rodents,56 many studies in humans demonstrated that acute stress impaired memory retrieval after a stressful encounter (refs 18,19,57,58,59 but see refs 60,61). Retrieval in the stressful situation itself seemed not to be affected or even enhanced,18,19 particularly when retrieval performance was directly relevant to the stressful encounter. Retrieval more than 20 min after stress, however, when cortisol levels were already elevated, was impaired by the cortisol response to stress18,19,58 (Figure 3) and the impairment appeared to be even stronger at a time point when genomic cortisol actions had developed,18 suggesting that the impairing effects of stress can last much longer than previously known. This retrieval deficit after stress was not only found in adults but was also observed in 8–10-year-old children, highlighting the relevance of these findings for educational settings.59 The disrupting effect of stress on retrieval was stronger for emotional material26,62 and also the context appeared to play a moderating role on the effects of stress on retrieval. For instance, if the retrieval test was relevant for the stressful situation or if both learning and test took place in the same context, so that the context served as a retrieval cue, recall was spared from the impairing effects of stress.19,63

Figure 3

Stress impairs memory retrieval. Participants learned a two-dimensional object location task similar to the game ‘concentration’ (note that for illustrative purposes encoding is depicted by a book, similar to studying in class). One day later, participants either underwent a mild stress induction procedure (indicated by the red flash) or a non-stressful control procedure before recalling the card pair locations learned on day 1. Participants in the stress group recalled significantly fewer card pair locations on day 2 than participants in the control group (relative to their performance on day 1), indicating that stress before retention testing reduced memory performance. Adjusted, with permission, from ref. 63.

Full size image

The negative effect of stress on retrieval could be mimicked by administering a GR agonist and blocked by the cortisol synthesis inhibitor metyrapone in rodents, which suggests a GR-dependent pathway43,56,64,65 reducing blood flow in the medial temporal lobe.66 However, the interaction with NA appears to be crucial as the impairing effects of cortisol depended on noradrenergic activation of the amygdala.52 For instance, blocking the action of NA pharmacologically with propranolol abolished the impairing effect of cortisol on emotional memory retrieval.67 Thus, similar to memory consolidation, the interaction between GR-mediated cortisol action and NA appears to be crucial for stress-induced effects on memory retrieval.67

To summarise, stress affects memory in a time-dependent manner, often enhancing memory formation around the time of the stressful encounter but impairing memory retrieval and the acquisition of information encoded long after the stressful event. These effects depend on interactions between NA and cortisol in the amygdala and are thus often stronger for emotional than for neutral learning material. In the next paragraph, we will move beyond stress-induced changes in memory performance and describe how stress may also affect the integration of new information into existing memories, i.e., knowledge updating.